Shell Heaps

A Coastal Archive on the Kennebunk River

“Middens are an archive of ancient coastal lifeways and environments.”

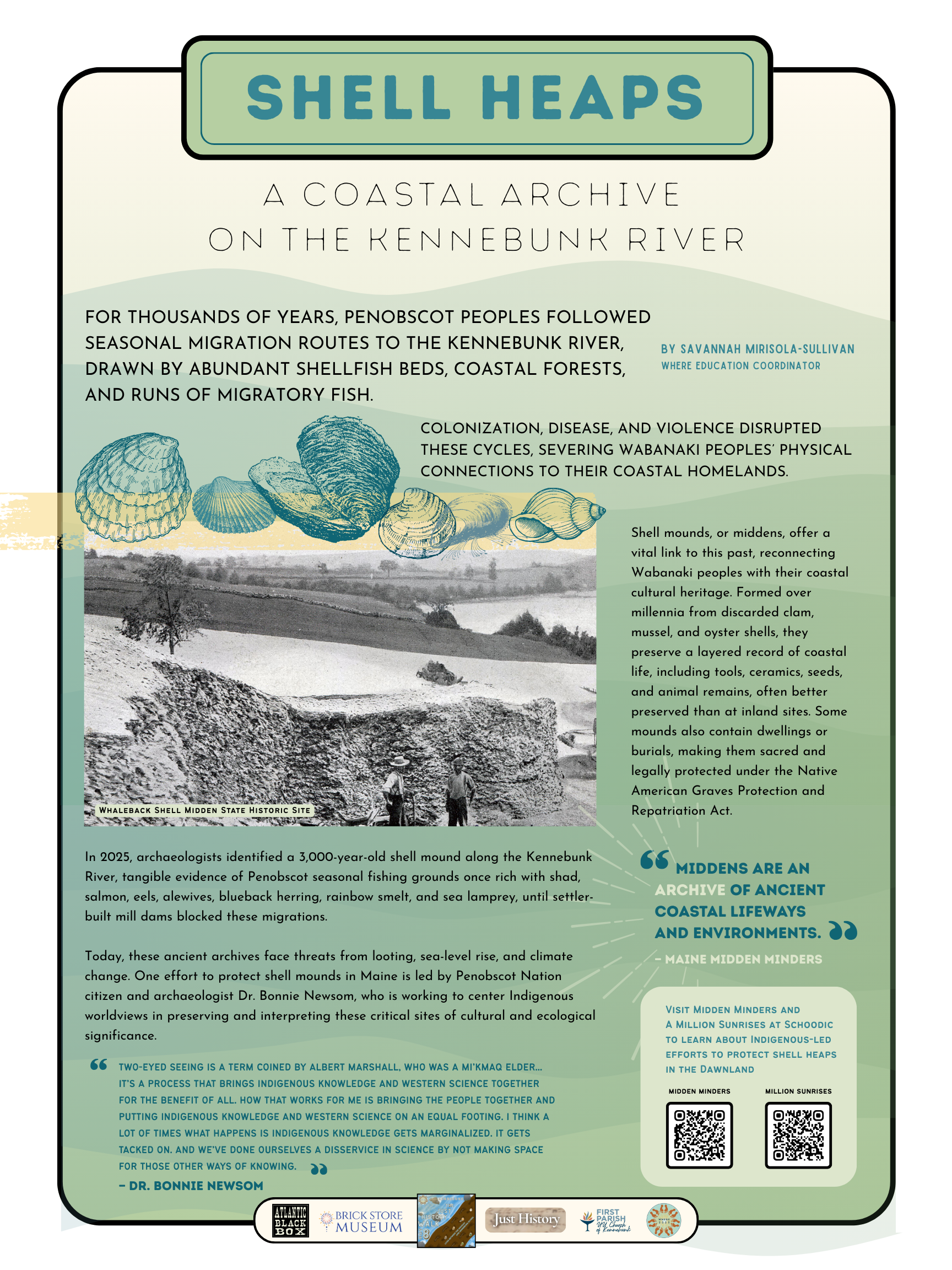

Whaleback shell midden state historic site in Damariscotta.

“The other thing that really inspired me was having the opportunity to connect with my heritage and ancestors through their material world...I wanted to help tell that story. And I wanted to reconnect with my ancestors. I think archaeology can provide a pathway for other people in our community to reconnect.”

For thousands of years, Penobscot peoples followed seasonal migration routes to the Kennebunk River, drawn by abundant shellfish beds, coastal forests, and runs of migratory fish. Colonization, disease, and violence disrupted these cycles, severing Wabanaki peoples’ physical connections to their coastal homelands.

Shell mounds, or middens, offer a vital link to this past, reconnecting Wabanaki peoples with their coastal cultural heritage. Formed over millennia from discarded clam, mussel, and oyster shells, they preserve a layered record of coastal life, including tools, ceramics, seeds, and animal remains, often better preserved than at inland sites. Some mounds also contain dwellings or burials, making them sacred and legally protected under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.

In 2025, archaeologists identified a 3,000-year-old shell mound along the Kennebunk River, tangible evidence of Penobscot seasonal fishing grounds once rich with shad, salmon, eels, alewives, blueback herring, rainbow smelt, and sea lamprey, until settler-built mill dams blocked these migrations.

Today, these ancient archives face threats from looting, sea-level rise, and climate change. One effort to protect shell mounds in Maine is led by Penobscot Nation citizen and archaeologist Dr. Bonnie Newsom, who is working to center Indigenous worldviews in preserving and interpreting these critical sites of cultural and ecological significance.

“Two-eyed seeing is a term coined by Albert Marshall, who was a Mi’kmaq elder... It’s a process that brings Indigenous knowledge and Western science together for the benefit of all. How that works for me is bringing the people together and putting Indigenous knowledge and Western science on an equal footing. I think a lot of times what happens is Indigenous knowledge gets marginalized. It gets tacked on. And we’ve done ourselves a disservice in science by not making space for those other ways of knowing.”

Additional Resources:

Visit Midden Minders and A Million Sunrises at Schoodic to learn about Indigenous-led efforts to protect shell heaps in the Dawnland

Learn about contemporary policies to allow for the culturally sensitive return Indigenous remains (some found in shell heaps)

This research was compiled as part of the Just History Walk: Lives Between Two Rivers, which took place on November 8, 2025. For more information about this walk, click here. For more research related to this area, click on the tags below. To download a hi-res version of the poster below for educational use, please contact where@atlanticblackbox.com.

Poster design by Meadow Dibble