What If It Was a Canoe?

A Journey in Trusting the Process

Timelapse by James Eric Francis, Sr.

Each WHERE walk is made up of many parts—among them: route planning, research and stories, food, logistics, relationships, and creative elements. The flow of all the programmatic elements and how the creative threads come together is often one of the last pieces of each walk to come together, sometimes much to each partner group’s chagrin.

One of my primary roles as Creative Coordinator is to walk alongside each group and provide reassurance that all is well while we are in the protracted discomfort involved in the creative process; the long stretches where we can’t yet see where we are headed, but we know we are on our way.

The creative event design committee team for the Castine Wayfinding Walk, which had merged with the education committee for the first time in the planning of a WHERE walk, was made up of Georgia Zildjian of the Wilson Museum, Nicholas Berry of the Witherle Memorial Library, WHERE’s Education Coordinator Savannah Mirasola-Sullivan, and myself. We had been meeting for several months and although ideas, thematic elements, and enthusiasm were abundant, the shape these elements would take was still not immediately clear. The walk was just one week away.

We knew we wanted there to be weaving–

to contribute/generate vs. absorb

to make the invisible visible

to illustrate a Wabanaki sense of place

James Francis (WHERE advisor, Penobscot Nation’s Director of Cultural and Historic Preservation, Tribal Historian, and Chair of Penobscot Tribal Rights and Resource Protection Board, historical researcher, photographer, filmmaker, painter, and graphic artist, and part of the team of Penobscot advisors helping the town of Castine with an interpretive plan) wanted to see Fort Pentagoet outlined, to see its footprint on the earth.

Initially, we thought the weaving would happen at the fort, but I couldn’t wrap my head around why we would re-weave a colonial structure. James joined us at our last creative committee meeting, and I asked him to explain—again—why it was so important to visualize the fort. I didn’t get it. As a non-native person in the ongoing process of grappling with settler/native relations and histories in this place, I had learned narratives of forts and trading posts* being purposely placed by colonists to interrupt sustenance and important cultural sites, and that was the sole lens from which I was seeing.

“This fort is a place to honor Indigenous presence,” James said.

The weaving was to honor the relationships. Baron Jean Vincent de St. Castin and Madockawando. The French and the Penobscot, whose bloodlines and legacies live on today on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. Forts and trade houses were utilized by Wabanaki people as they shaped a new way of life through trade. These layered stories are forever woven. I am certain James had told me this before, but this time I was finally able to hear it.

With this understanding, generative questions started sparking:

What if we outlined the footprint of the fort with a material that participants could then deconstruct and use as weaving material later?

What if we offered weaving materials at each stop along the walk, related to stories shared, to honor the connectedness of all these stories?

And, what could we weave them all into together at the end?

“What if it was a canoe?” asked James, in his characteristically concise-yet-poignant way.

Everything that had been swirling in the air for months came down to earth. The energy shift was palpable, even on Zoom. After the meeting Savannah (WHERE’s Education Coordinator) texted, “I feel SO excited about this new plan, and like it pulls together so many loose threads to beautifully represent this walk. Yay!”

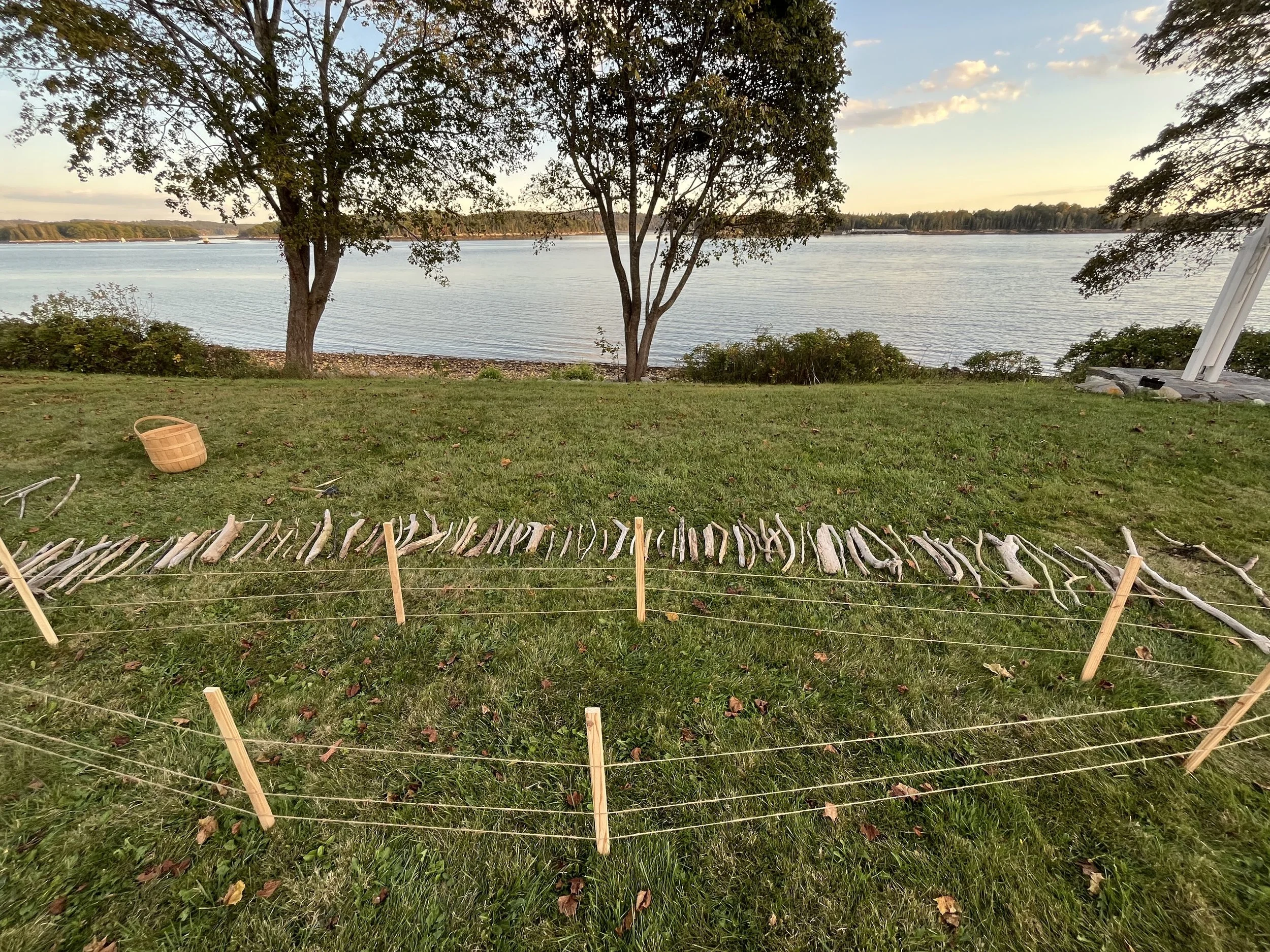

We built the frame for the canoe at full scale on the lawn outside the Wilson Museum,

from driftwood gathered on the shoreline below.

We later learned that the frame we built resembled the first steps of the process of building an actual birchbark canoe.

At the beginning of the walk a prompt was given, inviting people to gather weaving materials, carry them along, and imbue them with what they were learning, thinking, and feeling.

And so it was.

Walkers picked up strands of rope and indigo dyed cloth from West Africa at the waterfront, where Doc Flo Edwards spoke about the re-naming process of Esther and Emmanuel islands…

and pieces of red wool fabric–a facsimile of the red wool trade cloth that became a vital commodity in global trade during the 18–19th century–at Dyce Head, where Jennifer Neptune shared the story of how Gluskabe’s snowshoe prints came to crisscross the rocks below.

In the spot where Fort Pentagoet once stood, James spoke about his dear friend Charles Norman Shay and the woven histories of French nobility and the Penobscot Nation and then invited everyone to dismantle the fort.

With varying degrees of joyful defiance and gratification, walkers ripped, tore, tugged, and pulled down every last line of neon flagging, wrapping it around them or sticking it in their pockets as we continued on to the next stop on the journey.

When the walkers arrived at the last stop and saw the driftwood canoe frame waiting for them, they knew just what to do.

No instructions were needed.

Young and old gathered around its frame, kneeling inside and out, quietly weaving together.

Magic hour showed up to help, as did Firefly, singing to us and leading us in a round dance.

James and I stood back, smiling at each other, and proudly watching the walkers as they joyfully interwove historical threads into a contemporary artistic interpretation of a traditional Wabanaki form that has graced the banks of the Bagaduce River for thousands of years. It worked.

In the week following the walk, Nick from the Witherle Memorial Library kept tabs on the canoe.

“I took a couple pictures of the canoe as I drove by this morning,” he shared.

“These are great, Nick!” I replied, grateful for his commitment to our shared creation. “The dappled morning light really suits her. ✨ ”

*Sutton, Anthony, and John J. Daigle. From the St. Croix to the Skutik : Expanding Our Understanding of History, Research Engagement, and Places. 2020. Thesis (Ph.D.) in Ecology and Environmental Sciences—University of Maine, 2020.

Bonus Photo Gallery

These photos are just a small few of many photos taken before, during, and after the walk. There are more photos of this dynamic, many-layered walk to come.

This research was compiled as part of the Mači-pikʷátohsək: A Wayfinding Walk which took place in Castine on October 5, 2025. For more information about this walk, click here.

For more research related to this area, click on the tags below. To download hi-res versions of the posters for educational use, please contact where@atlanticblackbox.com.

This event was a collaboration between Castine History Partners (CHP) and the Walks for Historical & Ecological Recovery (WHERE), a series convened by Atlantic Black Box. Castine History Partners is a collaboration originally established to create virtual history tours for Castine. CHP supports a variety of learning opportunities around the history of Castine. The partners include Castine Community Partners, Castine Historical Society, Castine Touring Company, Maine Coast Heritage Trust, Maine Maritime Academy, Wilson Museum, and Witherle Memorial Library.