Poster Lesson Plan

Out of Archives, Into the Classroom

In partnership with the Walks for Historical and Ecological Recovery (WHERE), local groups across the Dawnland have surfaced and shared a wealth of community-driven research to answer the question: what happened here?

Much of that historical research lives here in the WHERE digital archives. We encourage educators to use and adapt the resources in the archive in service of place-based learning informed by the collaborative, process-oriented approach that shaped the WHERE walks. This lesson plan template is one possible tool to support educators in planning and iterating how the research from the walks can be made accessible for learners of all ages,

The WHERE walks are designed with many of the same principles that anchor place-based learning, such as:

surfacing historical truths about what happened in a place

allowing learners to engage with their hearts, minds, and bodies

offering multiple modes of access (informational text, video, music, performance, hands-on or embodied experiences, connecting to emotion, conversation, storytelling, art making, community speakers, relationships)

learning about local environments and ecologies

centering the voices of Black and Indigenous communities, cultures, wisdom, experiences, and worldviews

necessitating collaboration

deepening relationship to place and community

moving beyond the walls of the classroom and other institutions

Using the Archives as an Educator

The lesson plan template is intended to be used in conversation with the WHERE archive, which contains place-based historical research, primary sources, maps, additional links and resources, and examples of creative, artistic engagement. When using the archive for lesson inspiration, you might focus your search by location, or by topic. The texts, posters, and images shared on the archive are open-source, and can be downloaded to revise and adapt for use in your classroom or learning space.

Adapting the Research

For work with students in grades K-8, you may decide to adapt the poster/archive text so that it is accessible for younger readers. To do so, you can simplify or define vocabulary, shorten sentences, break up longer paragraphs into smaller chunks, add clear headings, pre-teach certain vocabulary/names/concepts, create a timeline, connect to prior learning, and use strategies for shared reading. Here’s one example of how to adapt a poster for 4th grade readers:

Original Poster Text:

(original poster & research located here)

Not everyone who fought in the American Revolution did so by choice. At least five Black men from Kennebunk and Wells served in the Continental Army, though the records reveal little about their lives. Some were likely enslaved; others may have been free. We do not know if they enlisted voluntarily, were forced by enslavers, if they ever received the bounties and pay promised to them, or their freedom after the war.

Free and enslaved Black residents would have heard talk of liberty and equality proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence, yet they lived under systems that denied those very rights. They faced impossible choices:

Fight for the Patriots, hoping freedom would follow victory.

Join the British, who explicitly promised emancipation.

Or resist enlistment and await the war’s end.

American victory in the Revolutionary War led to changes in the Massachusetts state constitution. In 1783, Quock Walker, an enslaved man in Massachusetts, leveraged these shifting legal parameters to successfully argue that slavery was now outlawed in the state. His case, and two others, provided the basis for emancipation in Massachusetts and what is now Maine.

Although the legal status of Kennebunk’s enslaved people changed following emancipation, the confines of their lives often remained the same for decades to come.

Archival records tell us that at least five Black men from Wells and Kennebunk served in the American Revolution, all of whom are included in the Just History Database. Together, these fragmented stories reveal the limits of what written history preserves about Black lives in the region, and remind us that Black men fought for a nation that continued to deny them freedom.

Salem Bourne

Salem (later known as Salem Bourne) enlisted in 1778 at age 23, and served in the 1st York County Regiment. His unit was sent to Fishkill, New York to a major supply depot. At the time, he was enslaved by shipbuilder John Bourne of Kennebunk. Whether Salem enlisted voluntarily remains unknown.

Primus Goodale

In 1781, the Wells Selectman paid a bounty to Primus Goodale to serve in the Revolution for three years. Born in “Guinea” (West Africa), he was a mariner when he enlisted at age 36. Records list him in the 7th Massachusetts Regiment at West Point, but do not reveal if he was free or enslaved. The name “Joseph Goodale,” possibly his enslaver, appears in related documents, but the connection remains uncertain.

Scipio Black

Scipio enlisted early in the war in 1775, serving in Captain Samuel Sayer’s Company as part of the 30th Regiment of Col. James Scammon. Scipio was stationed with his company in Cambridge, Massachusetts for 25 days.

Scipio was enslaved by Dr. Joseph Sawyer of Wells. While some records show the name “Scipio Black,” others list him as “Sippo, Black.” This suggests that "Black" was a statement of his race rather than his last name. It may have been thereafter utilized as his last name.

Shepard

Shephard, whose last name was not recorded, served as a private in Captain Samuel Sayer’s Company from Wells, like Scipio Black. He fought in the 1779 Penobscot Expedition at Fort George in what is now Castine, Maine. Shepard survived intense fighting where his commander, Samuel Sayer, was killed.

Cesar

Simply recorded as “Ceser, Negro” is listed as a soldier from Wells. Nothing more is known about his life or service.

Reflection Questions:

What questions would you ask these five men if you were able?

Why might so many details about the lives of these men be absent from archival documents? Why was certain information recorded in the archives, while other information was not? What value systems can archival documents reveal?

Adapted Poster Text:

Whose Freedom?

The Declaration of Independence says that “All men are created equal,” and promises “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” These words were written in 1776, They inspired many people to join the Patriots and fight against the British.

But was this promise of equality and freedom meant for everyone?

Slavery in Kennebunk and Wells

During the American Revolution, Black and white people in Kennebunk and Wells were not treated equally. Most Black people in the area were enslaved.

Enslaved people were forced to live with and work for their white enslavers. They were not paid for their work, and did not have freedom. They were treated as property instead of people.

An Impossible Choice

When the American Revolution began, Black men had to make a very hard choice:

fight for the Patriots, hoping to get their freedom

join the British, who promised freedom

not join either army, and wait for the war to end

At least five Black men from Kennebunk and Wells served in the Continental Army against the British.

Black Soldiers: What We Know and What We Don’t Know

There are only a few records from the American Revolution that tell us about these five soldiers. Because of this, there is a lot we do not know.

Some of them may have chosen to join the army. Others may have been forced to join by their enslavers. We do not know if they were ever paid for their service, or if their enslavers took the money that was promised to the soldiers. We also do not know if they became free after the war.

Here is what we do know about them.

Salem Bourne:

Salem joined the army in 1778. He was 23 years old, and was enslaved by a shipbuilder named John Bourne from Kennebunk.

Salem served in the 1st York County Regiment.

Primus Goodale:

Primus Goodale was born in West Africa. The records do not say if he was free or enslaved. However, because he was born in Africa, it is likely he was stolen from his home and forced into slavery.

Primus worked as a sailor. He joined the army in 1781 when he was 36 years old.

Scipio Black:

Scipio joined the war in 1775. He served in Captain Samuel Sayer’s Company. His group traveled to Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Scipio was enslaved by Dr. Joseph Sawyer in Wells. In some records, his name is written as “Scipio Black.” In one record, it is written as “Sippo, Black.” We don’t know if “Black” was his last name or how his race was listed.

Shepard:

Shepard’s last name is unknown. It may never have been written down.

He served in the same company as Scipio Black In 1779, Shepard fought in a battle called the Penobscot Expedition in Maine. Indigenous soldiers also fought in this battle against the British. Their goal was to take Fort George from the British.

The battle was dangerous, but Shepard survived..

Cesar:

Very little is known about Cesar. We only know his first name. He was a Black soldier from Wells.

After the War

After the Patriots won the war, laws began to change in Massachusetts. Maine was still part of Massachusetts at that time. In 1783, an enslaved man named Quock Walker went to court to fight for his freedom. He argued that slavery was now illegal in the state.

His case helped lead to emancipation (the end of slavery) in Massachusetts (and Maine).

Even though slavery was now illegal, the lives of Black people in Kennebunk did not improve right away. Emancipation did not mean equality.

Reflection Questions

Why do you think we know so little about these five soldiers?

If you could talk to these soldiers, what would you ask them?

What would you want to say to them?

Glossary

Continental Army – The army that fought for the American colonies during the Revolution.

Regiment – A large group of soldiers.

Records – Papers or documents that give information about the past. Primary Sources.

Expedition – A military journey or mission with a goal.

Emancipation – Freedom from slavery.

MOOSE Learning Progressions

The template can support you in creating a complete unit, or individual lesson plans to embed into your existing curriculum. It also encourages you to consider how the poster and archive content might align with MOOSE Learning Progressions, another open-source tool for educators. Much of the poster content pairs with at least one of the following units:

K–2nd Grade

What do you know about the Wabanaki and their languages? (K-2nd)

Helping My Community in a Changing Climate (K-2nd)

How Do You Get Around Maine?(K-2nd)

Why is my Climate Changing? (K-2nd)

Forest Fun(K-2nd)

3rd–5th Grade

The Wabanaki and the Environment: Learning to Use My Voice Through Activism Today (3rd-5th)

Exploring Boundaries, Resistance, and Advocacy (3rd-5th)

How Does Culture Shape Celebrations? (3rd-5th)

Data is Beautiful: Making an Impact with Visual Data(3rd-5th)

Nature Observing For Climate Change(3rd-5th)

If These Walls Could Talk(3rd-5th)

6th–8th Grade

What Do I Stand For? The Journey to Becoming a Changemaker (6th-8th)

How Do You Choose To Do What is Right? (6th-8th)

Exploring Empathy and Advocacy (6th-8th)

Migrations to Maine: Stories from Maine's African Diaspora History (6th-8th)

Is climate change affecting invasive species in ME? (6th-8th)

Stirring Up Stories: Exploring the stories, flavors and people that make your recipes special (6th-8th)

Wabanaki Stewardship: Our Relationship to Water (6th-8th)

Life of Trees ~ Trees of Life: Do we need trees or do trees need us? (6th-8th)

9th–12th Grade

The Art of Allyship: Partnering with Wabanaki Conservationists for a Better Tomorrow (9th-12th)

Achieving Sustainability Through Policy (9th-12th)

Field Notes for Maine Climate Solutions (9th-12th)

How can we address the unequal burden of our changing climate? (9th-12th)

Wabanaki Homelands: Culture & Identity (9th-12th)

How do we make meaningful connections between people and their climate? (9th-12th)

Moving Beyond A "Single Story": Inclusive Storytelling (9th-12th)

African Diaspora Art in Maine (9th-12th)

Invasive Species, Native Species -- Who Cares? (9th-12th)

Where Do I Fit? Finding My Place in the Global Community (9th-12th)

How Can I Be Brave? (9th-12th)

How can I understand and impact my town's climate story? (9th-12th)

Wabanaki Artists (9th-12th)

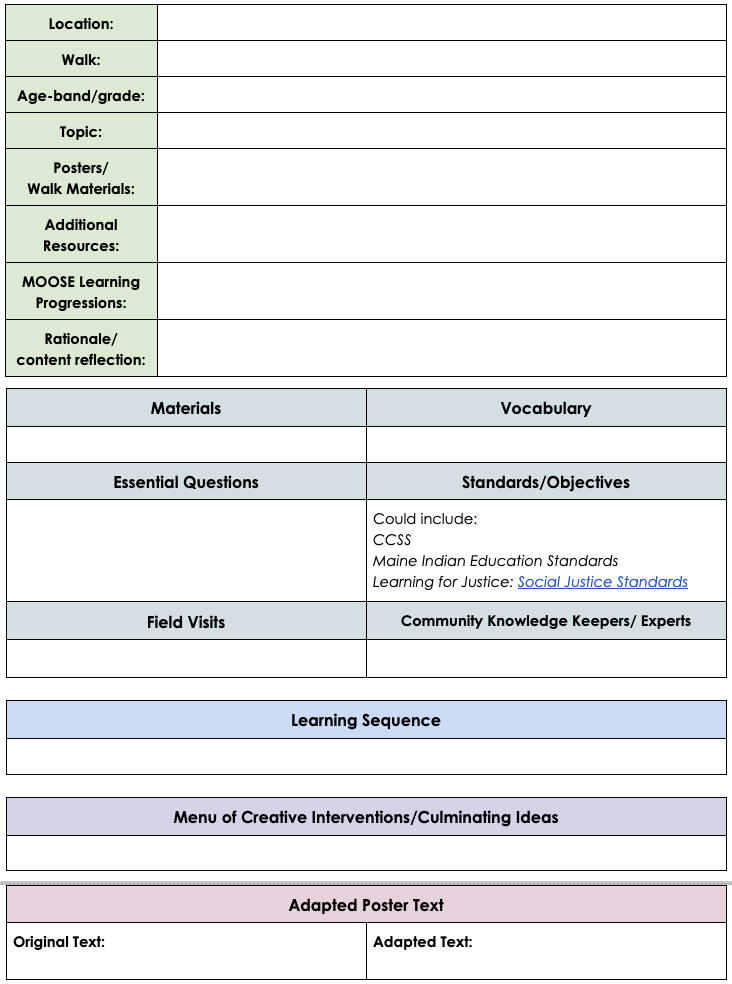

The Template

When you click on the template below, it will open a new google doc and prompt you to make your own copy. Revise and customize the template to meet your needs!