The Nicolar Family

Survivance across the Dawnland

This research was compiled by Savannah Mirisola-Sullivan & Tahloni Yearwood with thanks to James E. Francis, Sr.

Back row L-R: Leo Shay, Howard Ranco, Roland Nelson. Front row: Bruce Poolaw, Lucy Poolaw, Florence Nicolar Shay and Charles Shay (who was known as Little Muskrat when he danced). Photo courtesy of Charles Normal Shay.

“Survivance: beyond mere survival, survivance is interpreted as active resistance, endurance, and self-definition in the face of settler colonialism, forced-assimilation, and erasure. ”

The theme of survivance extends through every branch of the Nicolar family tree.

Young Florence Nicolar Shay

After hundreds of years of colonial displacement, the Nicolar family reclaimed their ancestral seasonal camp at the mouth of the Kennebunk River, where they actively reshaped their traditions in response to current societal realities.

Elizabeth Nicolar and her husband Joseph had three daughters, Emma, Lucy, and Florence. They raised their children on the Penobscot Reservation on Indian Island, and traveled to Kennebunk and Kennebunkport with other Penobscot and Passamoquoddy families each summer from the 1880s to the 1930s. They adapted to the tourist economy by selling their sweetgrass baskets and performing in regalia.

“Survivance is an active sense of presence, the continuance of native stories, not a mere reaction, or a survivable name. Native survivance stories are renunciations of dominance, tragedy, and victimry.”

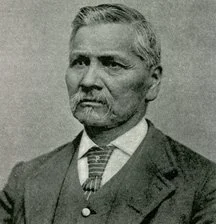

Joseph Nicolar

Joseph Nicolar served as the Penobscot Nation’s elected official to the Maine State Legislature for eleven terms. Joseph self-published his book “The Life and Traditions of the Red Man” in 1893 to preserve and pass on Penobscot cultural heritage. Elizabeth helped to found the Wabanaki Club of Indian Island in 1895, and taught her daughters to weave baskets.

Emma, Lucy, and Florence followed their parents’ examples of service and self-representation. Lucy and Florence traveled with their mother around the country sharing their celebrated baskets. They advocated for Indigenous children to attend public schools, and helped to build a bridge to Indian Island to increase their community’s access to schools and other resources.

The sisters were also instrumental in gaining long-overdue suffrage for Wabanaki peoples. Florence wrote to President Franklin Delanor Roosivelt to advocate for the right to vote. While Wabanaki people were granted the right to vote in federal elections in 1954, the right to vote in state and local elections was not granted until 1967.

“It is very apparent that Joseph and Elizabeth willingly took on the responsibility for the welfare of their people and were able to accomplish very much during their lives, all to the benefit of their family and their people.”

Reflection Questions:

How is the Nicolar family representative of broader Wabanaki survivance across the Dawnland?

Why did it take so long for the Wabanaki people to gain the right to vote?

Why have Wakanaki tribes in Maine been unable to gain the benefit of being governed by federal Indian law, even though every other federally recognized tribe in the U.S. is eligible for those benefits?

Sources

https://bipoc.brickstoremuseum.org/search/JosephNicolar/

https://bipoc.brickstoremuseum.org/search/ElizabethJosephNicolar/

https://bipoc.brickstoremuseum.org/search/LucyNicolarPoolah/

https://bipoc.brickstoremuseum.org/search/FlorenceNicolarShay/

https://bipoc.brickstoremuseum.org/search/EmmaNicolarRanco/This research was compiled as part of the Just History Walk: Lives Between Two Rivers, which took place in Kennebunk on November 8, 2025. For more information about this walk, click here. For more research related to this area, click on the tags below. To download a hi-res version of the posters below for educational use, please contact where@atlanticblackbox.com.

Poster design by Meadow Dibble

Poster design by Meadow Dibble