The Bourne and Kingsbury Shipyard, Shipbuilding, and Kennebunk Landing

Economies of Enslavement

“ There are two rivers—one called the Kennebunk… on which most of the ship-building is done… The other river is the Mousam… Ship-building and sea-faring life are the main occupations of the inhabitants. A merchant marine of over fifty ships is owned in Kennebunk, and there are many vessels built annually… In proportion to population, Kennebunk is second to none in the state for wealth.”

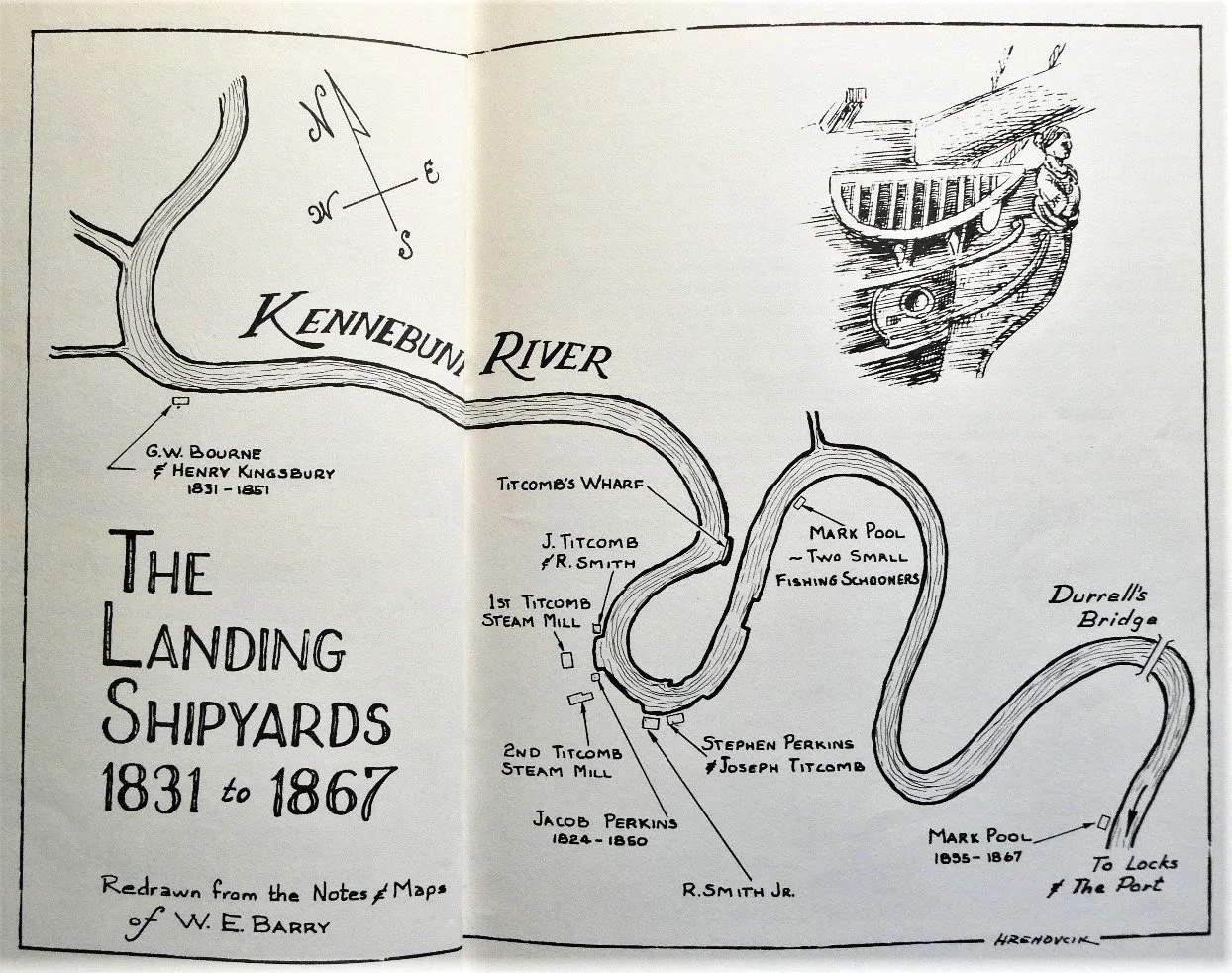

Shipbuilding remains a celebrated part of the identities of many coastal towns in Maine. It was the leading industry in Kennebunk for more than a century. At Kennebunk Landing, shipbuilding began in 1766, and many major shipyards flourished there. By 1830, those sites had produced almost 400 ships.

In 1831, two shipbuilding operations merged to form the Bourne and Kingsbury Shipyard on the Kennebunk River.

By the 1840s, voracious shipyards had depleted lumber in Southern Maine. To keep up with the demands of their shipbuilding contracts and circumvent future lumber scarcity in Northern Maine, Bourne and Kingsbury purchased land in Virginia so that they could begin importing timber. So great was the demand from Kennebunk shipyards that partner George Bourne relocated to Virginia to oversee the operation, where he relied on labor from enslaved peoples on neighboring plantations to harvest the timber.

Locally built and owned ships from Kennebunk Landing traveled to the West Indies to trade up until the 1840s. These vessels carried hay, salt cod, flour, vegetables, lumber, and manufactured goods to the Caribbean, and returned with rum, molasses, sugar, coffee, and salt, almost all of which were produced by enslaved labor on West Indies plantations.

This trade was woven into almost all aspects of the local economy. The majority of Kennebunk families would have had a hand in this trade, whether they were merchants, investors, captains, sailors, yard workers, shipbuilders, farmers, fisherpeople, rope or sail makers, coopers, lumberpeople, or bankers. Despite the illegality of slavery in Maine at the time, Kennebunk’s wealth was reliant on the institution of slavery.

From The Landing - A Remembrance of her People and Shipyards by Thomas W. Murphy (1977).

The Kennebunk Customs District served Kennebunk, Arundel (now Kennebunkport), Wells, and Cape Porpoise, and recorded exactly 1,000 ship arrivals between 1800 and 1867, the majority of which were from the Caribbean before the year 1847. The combined population of these towns averaged approximately 7,000 people in this period.

Totals:

Sugar: 7,334,332 pounds

Molasses: 2,417,613 gallons

Rum: 2,427,693 gallons

Coffee: 3,396,851 pounds

Salt: 12,276,772 pounds (5,762,420 from the Caribbean; 6,514,352 from Europe and Canada)

All of these Caribbean products were produced by enslaved labor under brutal conditions, with the exception of about 2.5 million pounds of coffee, which came from Haiti after the revolution and the end of slavery there.

This research was compiled as part of the Just History Walk: Lives Between Two Rivers, which took place in Kennebunk on November 8, 2025. For more information about this walk, click here. For more research related to this area, click on the tags below. To download a hi-res version of the posters below for educational use, please contact where@atlanticblackbox.com.